Dear students of Biological Sciences.

I must say, you are looking exceptionally intelligent and ravishing today, I love what you did with your hair.

Now they do say:

Flattery is telling people what they already know about themselves

I won’t flatter you anymore and will instead be telling you awesome things about you that you don’t know. Firstly, you are reading a blog about just what an awesome life you can lead with the skills you already have. As long as you make the right decisions at the right time, anything is possible and that’s just a case of having the right mindsets that will influence your decisions.

Decision 1. Keep reading ;-]

That was easy.

I’m going to tell you things you learnt during your degree that you might half know already, things that you had no idea about, and why you can win at everything. Followed up by a few rules for life to help make the most of the skills you didn’t know you already had.

Now let’s dive into some more pre-amble self-qualification so you can understand where the hell this advice is coming from.

Who is Sam?

I studied Biology BSci 2010-2013 and had the honour of Gary Foster as my Tutor, Clare Grierson for my mini-thesis project and Alistair Hetherington for my research project. I couldn’t have asked for a more brilliant set of human beings. Sadly, I was rather pre-occupied from my studies due to starting a business at the same time, before I go too far into the details it was basically Deliveroo before Deliveroo. I did pretty well out of it in that it didn’t fail, I employed actual humans and made stuff happen reliably and somehow sold it. But I’m not yet a millionaire which is woefully unimpressive. I managed to not fail my degree and learn some useful stuff from it.

Since uni I have done an array of things mostly highly unrelated to Biology.

The two things most related to biology:

- Working in AI (artificial intelligence) measuring human emotions by tracking biomarkers (facial expressions, voice intonation, sweat response, heart-rate etc…). This was used for learning how to make interesting experiences for TV, advertising but will be increasingly used for creepy stuff. (We started building lie detection during credit card applications that could detect micro-expressions. In the future Netflix will know exactly how you felt about every movie you watch and just what the best movie for you right now will be based on how you are feeling.)

- Working on oil rigs developing new software for controlling and improving their operations. This helped reduce the amount of gas being flared and the amount of oil going overboard due to poor separation processes. (Amazingly a new species of crab was found on one of the rig legs whist I was there but it had nothing to do with me. I also saw a pack of killer whales once but mostly it’s just sitting in a metal box living groundhog day again and again and again and so on until the Gods allow you to go home. I don’t recommend it.)

Less related to biology I’ve learnt a lot about coding and marketing and I’ve travelled the world with highlights including:

- Toured North Korea

- Hitchhiked across Kazakhstan

- Being paid to sail around the Caribbean Lived in the woods of Tasmania for a month with zero technology (not even a watch)

- Spent ten days meditating in complete silence in India (no reading, writing, or even looking at other human faces – just deep exploration into your own mind)

I currently run the Growth Mindset Podcast where I get to interview some of the worlds most fascinating humans. From leading scientists to Olympic athletes, tech billionaires to an actual real-life Hitman. Since starting it two years ago, I now know the inventor of Siri, the founder of Graze, the guy who built the BBC iPlayer and one member of the team that discovered the Higgs Boson (and yes a hitman).

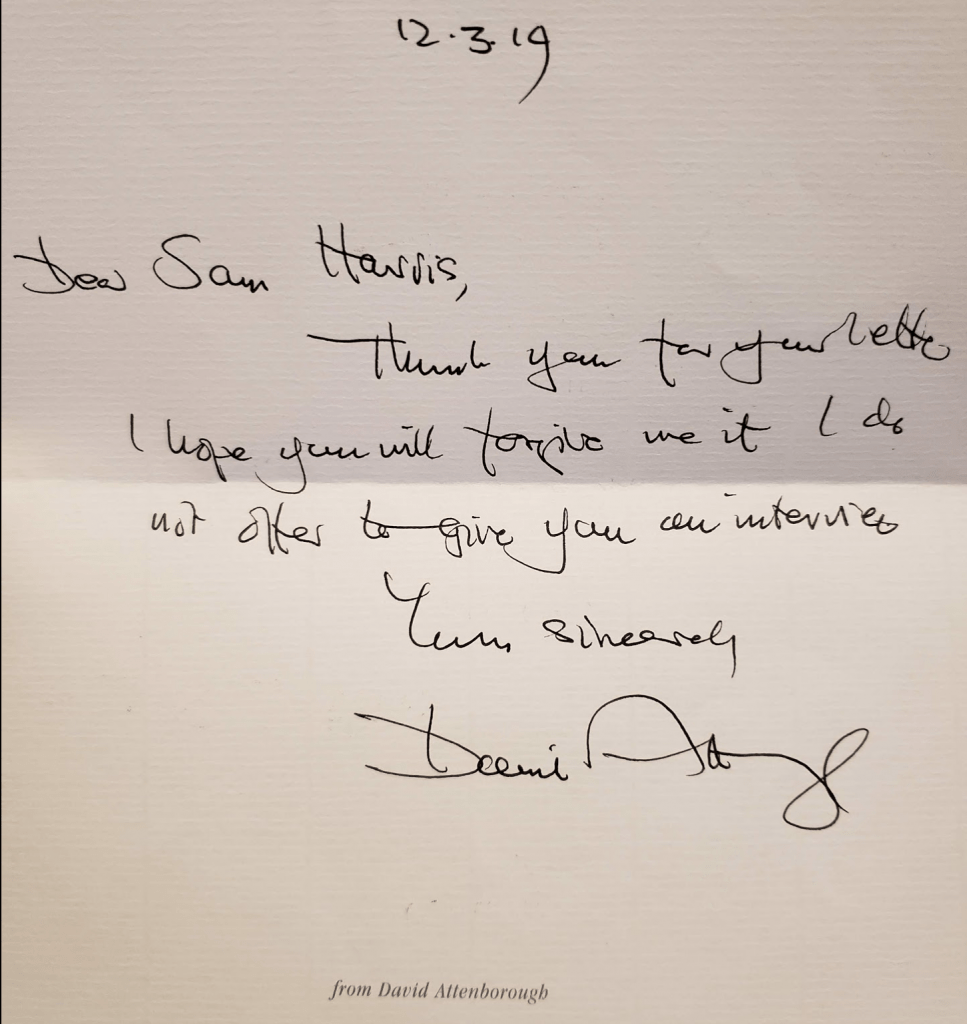

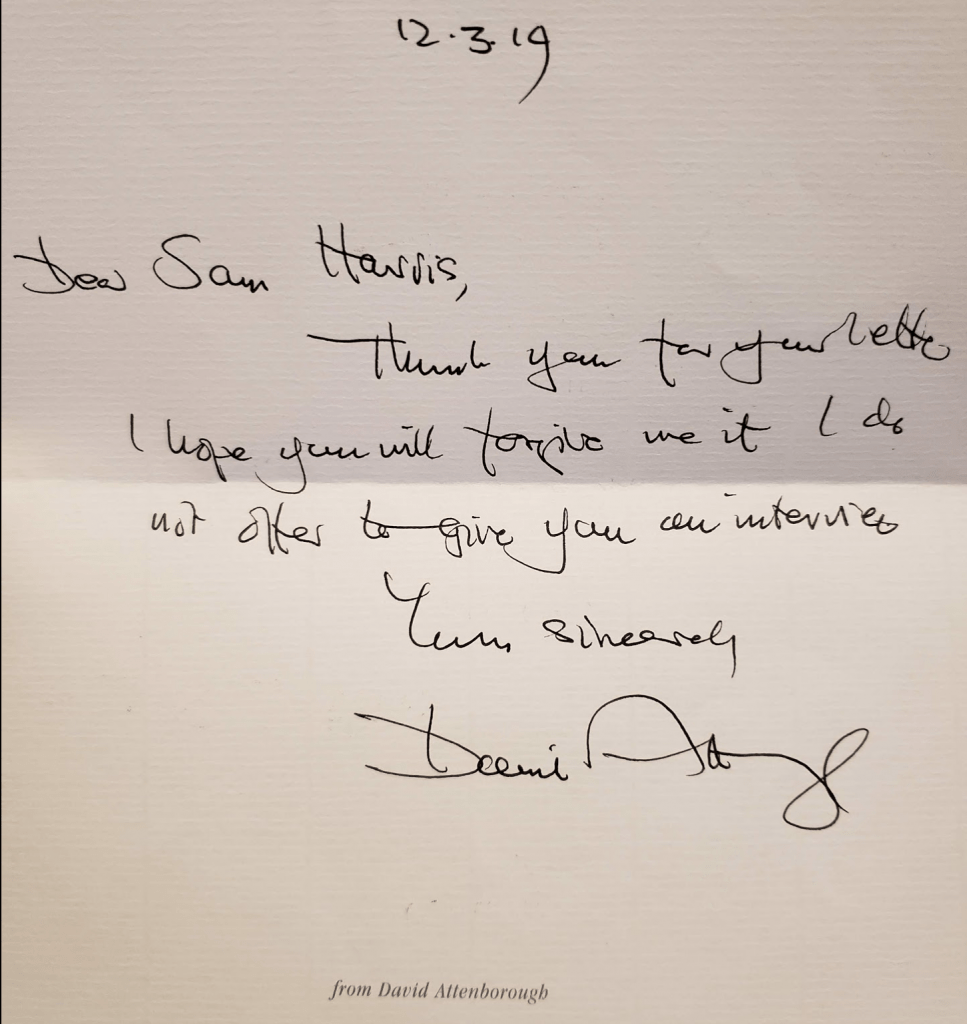

I’ve even exchanged letters with Sir David Attenborough himself.

This letter of rejection has now been framed by my mother (which she strangely hasn’t done with my degree yet).

Back to the point. I may have only left Bristol 5 years ago but I’ve learnt a lot about life so hopefully I can impart some wisdom on you that I wish I had known back then. In an ideal scenario, I might just save you the monumental amount of failing that I’ve done in the process of achieving these things.

The Value of a Biological Sciences Degree

Your degree is very important. But remember that it only opens doors for you (or perhaps more accurately it buys you a window of time to explain why you should go through the door.) You still have to deliver and generally be a useful person to be kept around in whatever you do. And there are other ways you can find to help open doors.

Some cool things that might not have been obvious that you can do with a degree in biology straightaway.

Like now: Start a Stupidly Cool business

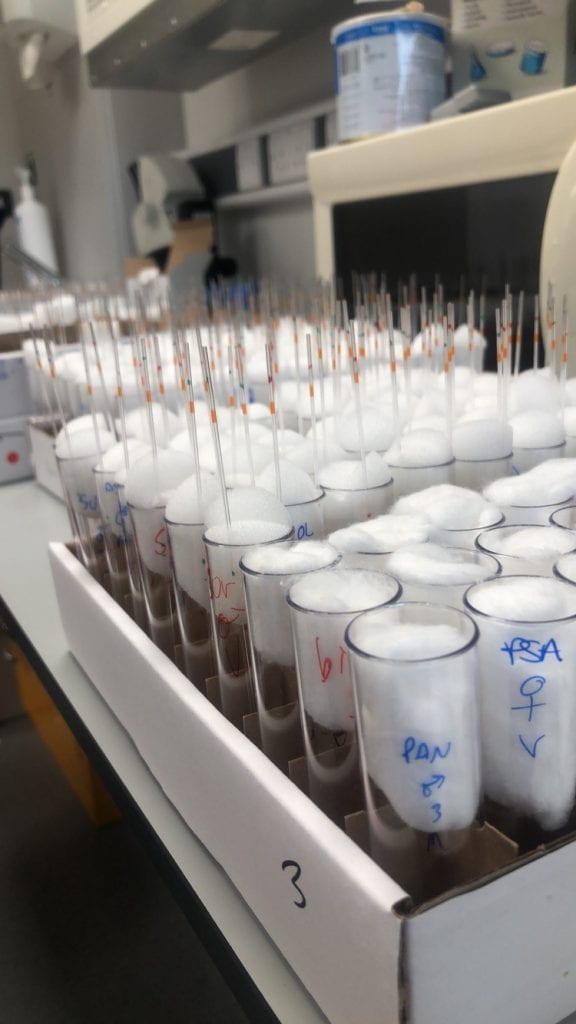

Biotech is the new big thing. Food innovation is hot, whilst Beyond Meat was the most successful launch on the stock exchange this year, even here in Bristol companies like Lettus Grow are doing super cool things. Deep Branch Bio are capturing carbon dioxide in industrial processes with bacteria that turn it into protein.

You don’t need years of experience to do this. Just research something that interests you and there is a whole team within the University to help you turn any inventions into a business (Basecamp Enterprise Team). You don’t need 20 years experience in industry before starting a business, people will take you seriously. Young people are considered smart these days, they’re unbiased approach to new ways of thinking is very valuable. You don’t need money, people give it to you to build your ideas, it’s pretty neat.

(see Anthony Rose Podcast for advice on how to raise money)

Save a Species and Save the Planet

For some reason conservation seemed like an awesome thing that I could never quite get round to spending a lot of time on. Documenting the decline of a species seemed rather depressing. I didn’t see how it really stopped anything bad from happening when you need to stop the economics of what is destroying the habitat rather than just measuring the resulting effects.

It turns out if you work in conservation you need to also get involved with the rest of the world. Tourism, politics and economics and then stuff actually starts happening. If you go and talk to leaders of countries with the right message you can get entire areas protected and national parks established with your work. Not only does this save species it also prevents deforestation and thus helps combat climate change all at the same time.

(see podcast episode with Dr Niall McCann about conservation and his work with National Park Rescue where he is actually doing this. He also finds time to get on TV and do mental things like rowing the Atlantic, skiing across Greenland and cycling the himalayas. My last email exchange with him was rather ‘snappy’ because he was busy rescuing alligators…If you want something meaningful to do you might find some life purpose helping them out)

Some cool things you definitely weren’t told about how great your degree is:

The Huge Value of being a Scientist:

Seeking truth is one of the most important things in life that humans happen to be terrible at. You would think that an intelligent ‘rational’ human would be open to new information that improves their knowledge about the world. But actually we much prefer to keep hold of the current idea in our head and use our intelligence to think about why the new information is wrong. (Confirmation Bias)

If you read a few different blogs about a topic that you have an opinion on, the ones that agree with your viewpoint confirm to your brain just how wonderful its opinions are. The ones that don’t agree must be written by idiots because your brain has a good view of itself and wouldn’t be wrong. (Confirmation bias in Online News)

If you can constantly challenge your thinking to seek truth, to cultivate a constant cycle of feedback and learning, then your life will be amazing. Your decisions will be correct so much more of the time, and whatever you choose to do, you will rise to the top because most humans can’t do this. (read books like Principles, by Ray Dalio, Creativity Inc by Ed Catmulll or biographies of Andrew Carnegie, Warren Buffet etc… The genius quality of these rich people isn’t that they are instantly correct about everything, it’s that they encourage other people to tell them when they’re being stupid and change accordingly).

If you have learnt anything from your degree I hope it is to scientifically seek truth. Look to find out exactly what is going on rather than seeking to prove your ideas right. It took me a long time and I genuinely always thought I had it fine because that’s how the ego works. In my third year Clare Grierson marked down my epic amounts of research due to being too selective. To this day, being sat in her office feeling like a melon is still the most memorable moment of my degree. Suddenly a whole tonne of things clicked into place. I sat there reflecting how much of an almighty idiot I was and I’d spent three years thinking I was doing something that I wasn’t.

Now just consider the vast number of papers published that show the writer had a great idea and proved it right, versus the number of papers that prove the writer’s idea was stupid. Being wrong is valuable information for future researchers. Science is still rather broken. Hopefully you aren’t.

How Biology Applies to Business:

I often get looks of surprise when people find out I studied Biology, this is swiftly followed by the question. ‘That has nothing to do with business. How did that lead into startups?

’The theory of evolution, adaption to the environment, competing for a niche to survive, game theory for optimal choice in partner selection or resource acquisition, the replication and proliferation of the genes which are the blueprint for a successful entity. This is all business, literally Biology is Business.

Companies are just individuals fighting for survival over scarce resources in their given niche. They are constantly evolving and adapting to change. Those that stay agile and quickly react to new opportunities proliferate whilst others die (e.g. Amazon became huge whilst Nokia disappeared).

A business franchise is literally just replicating the blueprint of a successful formula the same as replicating your DNA.

Not only do you know a tonne about business, you also know about Biology and Science which is more than any business graduate. Two degrees in one and no one ever told you!

Rules for Life

So you’ve learnt that you can start a business, save the world or get to the top of just about any field with your degree. Now some candid advice before you get too excited.

1. Focus

“You can do anything” does not mean “You can do everything”.

The Growth Mindset attitude is an amazing thing. It teaches us that with hard work you really can learn any skill, achieve greatness and constantly advance yourself.

It is important to remember that “hard work” actually means “focused work” and implies sacrifice of other things. You could spend your life working “hard” all hours of the day on a million different things, but you would only go backwards.

There’s a reason Mo Farah doesn’t compete in weightlifting, he’d be average at both running and weightlifting if he did. He also doesn’t “run” a business or “jog” patients back to life or “canter” through Netflix documentaries or “pace” himself through a long night out on the Triangle or “shuffle” his way through a PhD (or “lope” his way through awkward synonyms for “running”…). He just spends a lot of focused time training one skill and the rest of it smiling an inordinately.

2. Don’t Rush

The world is a brilliantly exciting place. There are also a million things you ‘could’ do and if you are doing one thing that leaves 999,999 things that you aren’t doing.You can quickly feel pretty inept when your Instagram feed shows a mate surfing in Bali, another getting a doctorate in curing cancer whilst another launched a million $ marketing business. This can lead to huge urges to quit what you’re doing and do something else that looks more fun.

Going back to the reflections on time earlier: If you are in your early twenties we can assume you will probably live until you’re 90, so that leaves almost 70 years to do all the things on your list. If you dedicated 7 years to each major project urge you are having, that is 10 projects you could go really deep on. You can really nail it safe in the knowledge that you can get down your list of awesome cool things that you will also nail. Now it seems pretty sensible that having a list of 10 projects you’ve completely bossed is better than a ridiculously long list of things that you started and stopped before you got any good at them.

3. Keep Learning

So you’re finishing education and about to embark into the world of actually doing stuff and becoming a productive member of society. Well actually your first 7-year task should be do more learning. Sorry.

It does slightly conflict with the ‘focus and only do one thing’ message, but try and learn as much as you can initially by working in different industries. Experience life in startups, corporates, science. See more of the world. Advice from the billionaire founder of Siri: never focus on money in any job you take and always optimise for learning. Whilst you’re young you can handle sleeping on a mate’s sofa and eating ramen etc… you don’t need money.

Money actually comes with it’s own set of problems and the whole overhead of managing it and not losing it which is another faff. It’s wise to acquire as much experience as possible and find out what you’re passionate about. You can learn what you would enjoy dedicating long periods of time to, when you’re older and more settled.

I don’t mean change what you’re doing every month. Do put time into actually doing the thing you’re doing. Just be open to trying different things that look interesting and get you out of your comfort zone. Switching it up every year or so till your 30s. By then you should have acquired a unique set of skills and can really start doing something you’ll smash out the park.

Just because you see people being ultra successful at 22 or whatever, you really don’t need to worry.

Firstly, remember that other people are irrelevant and the only thing that matters is that you keep on improving each day in comparison to yourself.

Secondly, 90% of these of ultra successful wizz-kid geniuses are actually just super lucky. In fact, I’d say I feel sorry for some of them because it goes to their heads and they genuinely start to believe their own crap and completely lose any ability to really seek truth and take on feedback (which was the all important quality I alluded to earlier). It took a while to realise that I am not a genius and that my first business took off due to sheer luck. Being honest, it was successful in spite of me and the number of mistakes I was continuously making rather than because of my innate business genius.

So now when I see a list of Forbes 30 under 30 etc.. I don’t think, “Oh God these people are so amazing and I’m such a failure”. Instead I think “Wow, look, a bunch of ridiculously lucky people who have no clue what they are doing but are under this weird illusion that they are geniuses. They’ll learn”

4. Respect Your Elders

As humans we are built to think pretty highly of ourselves and you should. If we lived in constant awareness of our ineptitude at almost everything we’d soon lose the Growth Mindset we should be cultivating. However, I think the gravity of how much more your elders know only hit me after leaving university.

The idea that you reach the phase of being an “adult” when you’re 20 is a very dangerous illusion. The bracket of working adults is 20-65 years old; thinking that this means you are on a level playing field is actually quite bonkers when you look into it.

My brain slightly explodes just trying to comprehend all the multitude of experiences and lessons I’ve learnt in the last 5 years. Trying to explain these things feels vastly more impossible than anything Tom Cruise has ever done (this includes the impossible achievement that for some reason I still like his movies which no amount of science can explain).

A few crushing realisations brought this about:

5. I am Stupidly Young

In my anticipation of David Attenborough’s sure to be wildly enthusiastic letter of acceptance, I thought about the fact he is 92. Collectively our combined ages add to 120 years of life experience. That’s impressive! But 71% of that is his experience. Him talking to me is directly equivalent to me talking to an 8 year old. This is rather humbling to say the least and made me feel like a baby.

Taking this a step further, we can look more broadly into the age of humanity or the earth and consider that your life is the merest blip on its timeline. You are literally just out of the womb with you eyes bulging at the monumentally mind-blowing phenomenon of taking a breath for yourself. And then that’s it, your life is already over.

Whatever you know now, a few years later you will look back and think of just how naive you were. This phenomenon never stops as you get older. Thus, you can conclude that your current self is an embarrassing idiot for your future self to deal with. This helps you take yourself less seriously, take others more seriously and forgive any mistakes of your own or others.

6. Other People Have Real Stories

There have been times when I’ve been asked to tell my own stories to people of stupid / genius things I’ve done and generally pass on fantastic wisdom. I often recognise a look of mild indifference that I know I used to have. Topics such as:Showing someone how to save their business from a huge mistake

The story of being unlawfully arrested in ParaguayGenuinely accepting my own impending death in the alps and being weirdly chill about it

Miraculously finding myself staying in a drug dealer’s house on the border of Mexico when I was trying to get to an organic farm to do some WOOFing.

All these things somehow didn’t seem to have the full gravity you’d expect.“Yea that’s cool but well. err whatever…”.

As young people we just seem to have this mild indifference the stuff older people tell us which causes them irrational annoyance. They will often wistfully accept that whatever they do there is nothing they can do to illustrate the importance of what they said or just how much it means.

This may sound weird, but it was at this point that I finally understood that other people’s stories are truly deeply real, whether it was exotic stories from a traveller, a business mentor explaining his mistakes or my grandfather talking about the war. It always felt a little, not quite ‘real’ when you’re younger and everything you’re told is just, well, a story. It took telling my own stories, and seeing them not quite sinking in, to recognise that there is so much behind the stories other people tell.

You shouldn’t just listen politely to others, you should listen with intense empathy and interest, and even if the subject means nothing to you, it means something to them.I made an interesting observation during my speech at the alumni event in the Biological Sciences building. All the other alumni with life experience seemed to really resonate with what I was saying. The students were visibly not so impressed by it. It’s not like they hated it, I guess it was just fine, whilst some of the alumni there were having ‘oh shit’ moments. But this makes logical sense. When I was young I wanted to play computer games all day and eat sweets and this seemed vastly important. Having my mum tell me that cleaning my room and doing homework was more important seemed odd and gave me the feeling she might be really stupid or something. Telling my friends 14 year old little sister that she doesn’t need to spend every hour on her phone messaging friends she’ll never talk to again when she’s older grants a similar reaction. It was about as effective as telling Trump the climate has issues that might be more important than building a big wall.

The point is that at every stage of life has different stages of what is important at that time and it can be hard to see other people’s viewpoints. As you get older you start to realise that any one who is older than you and tells you something they think is useful and interesting is inevitably always right.

7. Cherish Your Mentors

Now considering how young you are and how real and beneficial other people’s knowledge is, we can start to take onboard a lot more when we realise it is a resource to be treasured.

I really wish I had understood just quite how precious the delightful bundles of knowledge those people we call lecturers are. They have so much incredible experience in life, science, and just making things happen. The University just lets these insanely valuable entities wander around the department freely. What’s more, they will even talk to you if you ask questions, and to all appearances they seem to take you seriously. You can really make the most of them by finding excuses to get involved with anything you can, asking for advice and genuinely listening to it.

If knowledge were chocolate then the University is Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory: Do your best to fill your pockets before you leave.

Author: Sam Harris

Blog: www.SamWebsterHarris.com

Podcast: www.GrowthMindsetPodcast.com

Esme Hedley is a third-year year biology student with a passion for behavioural ecology, science communication and scientific illustration.

Esme Hedley is a third-year year biology student with a passion for behavioural ecology, science communication and scientific illustration.