How changes in colouration and behaviour enable marine arthropods to survive in a diverse environment

How changes in colouration and behaviour enable marine arthropods to survive in a diverse environment

Who is the hero of Professor Martin Stevens? As he told the staff and students of the university this Monday, it is the famous naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, who inspired Professor Stevens to pursue research into camouflage and colour in nature.

“Among the numerous applications of the Darwinian theory… none have been more successful, or more interesting, than those which deal with the colours of animals and plants” (Wallace 1889).

This Monday, the School of Biological Sciences was visited by Professor Stevens, who spoke about the mechanics of camouflage and its adaptive value in nature through studies of within-species diversity and habitat matching inshore crabs and chameleon prawns.

Camouflage seems like an easy concept to grasp.

We have all heard of the rapid colour change in chameleons. However, as Professor Stevens explained, it isn’t quite that simple. Firstly, the majority of colour change in animals is continuous and gradual, unlike that of the famous chameleons and cuttlefish. Additionally, this style of camouflage (background matching) is just one of many types that animals employ to disguise themselves in their environments.

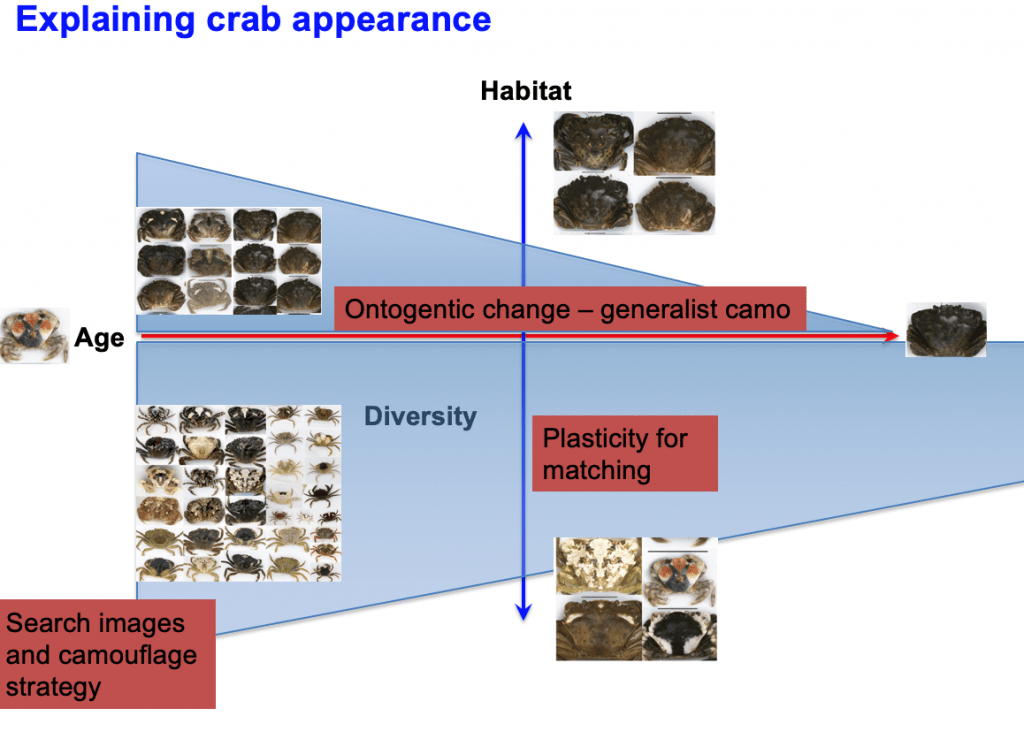

Professor Stevens elaborated on this in his case study of the common shore crab Carcinus maenas. This highly adaptable organism shows a huge variation in colours and patterns, which seems in part associated with background matching to the environment individuals are in. Both in mudflats and in rocky shores, the two differently coloured habitats we find these crabs in, the crab’s colour pattern is related to their habitat. Professor Stevens also revealed that crabs showed behavioural preferences to match to certain backgrounds as well.

Interestingly, these crabs also change appearance with age, gradually become duller and tending to lose their markings and converging on a universal dull green colour.

They seem to all adopt this generalist camouflage because while they get less mobile as they age, it might not be adaptive to keep matching the background if constantly moving; this strategy was found to be surprisingly effective, through analysis of a citizen science game at the Natural History Museum! Additionally, it was interesting to hear how individual diversity in these crabs is due to different camouflage strategies, such as disruptive colouration, and how complex markings can defeat predator search images and drive apostatic selection (i.e. rare appearances being more successful in avoiding predation).

Chameleon prawns (Hyppolyte varians) have even weirder and wonderful camouflage than the crabs, some being bright green, red, or transparent.

These creatures can change colour to match seasonal changes in substrate, although again this change takes 14-21 days; it is not quick like the chameleons! Therefore, some behavioural choices are needed to allow them to effectively camouflage in the short term. They seem to prefer seaweeds that match their body colour, and this is an effective strategy as survival rate has been shown to be higher on matched background. Parallels exist with a more exotic species in Brazil; nicknamed ‘carnival prawns’, the males can also be transparent, since they are less likely to sit on algae and are more mobile while in search of females.

Finally, Professor Stevens discussed questions for possible future study: Why do they change in colour at night? Why does light intensity affect the strength of camouflage? And, most intriguingly, can these prawns see in colour vision? To finish, the influence of anthropogenic change on these organisms was discussed in the context of how increasing water temperature and ship noise pollution might affect their camouflage abilities.

Written by Esme Hedley, Biology (BSc) and Miren Porres, Zoology (BSc)