“I’m still smiling!” was Professor Jane Memmott’s reply to being asked her feelings about becoming the newly-elected president of the British Ecological Society. In an office filled with shelves of books, a case of preserved butterflies, feathers from various species and a plant collection to rival the rest of the life sciences building, I interviewed Professor Jane Memmott on her career, interests and her journey towards the prestigious position she holds today.

“I’m still smiling!” was Professor Jane Memmott’s reply to being asked her feelings about becoming the newly-elected president of the British Ecological Society. In an office filled with shelves of books, a case of preserved butterflies, feathers from various species and a plant collection to rival the rest of the life sciences building, I interviewed Professor Jane Memmott on her career, interests and her journey towards the prestigious position she holds today.

Like so many of us, Jane’s lifelong fascination with nature began at an early age. It was during her childhood camping trips to County Clare in Ireland that Jane, inspired by her surroundings, developed an interest in ecology. In 1981, Jane began studying zoology at the University of Leeds. She described herself as a “keen and enthusiastic” student but mentioned that she still has “a horror of a few areas of biology from not liking them as a student!”. Jane went on to explain that it wasn’t until her third year at Leeds, when she really enjoyed everything she was studying, that she truly excelled as a student.

Professor Memmott took a year out after her BSc at Leeds, during which she took her first flight to Peru, where she worked as a tour guide in the Amazon rainforest for three months. This was Jane’s first taste of the tropics, and she became captivated by rainforests, leading her to write a PhD to be based in Costa Rica. Jane described one of her most memorable moments during her PhD in Costa Rica, when she encountered a sloth crossing the bridge of the field station. “They’re quite difficult things to catch- you can’t just unhook them from the handrail. We got it into a large dustbin and had the cutlery tray from the dishwasher over the top!” Once captured, the sloth was safely transported to a tree buttress to see what effect it would have on Jane’s experimental phlebotomine sandflies. Professor Memmott explained how she’d spent a lot of her life in tree buttresses, describing them as being “like a series of rooms around a big tropical tree.” The tropics can be a paradise for entomologists, and Jane recalled iridescent Morpho butterflies the size of dinner plates and giant damselflies that fly like helicopters.

“Jane described her endless fascination with understanding how the architecture of the network can affect pollination interactions and the robustness of the system to species loss.”

After her PhD in Costa Rica, Jane returned to the tropics for her first post doc. The project was to create the first food web to come out of the tropics, putting together a picture of the trophic interactions between the plants, leaf-miners and parasitoids of the rainforest community. This project got Jane hooked on studying ecological networks as a way of sampling whole communities. She explained, “rather than homing in on species x or species y, you kind of look at the whole alphabet at once.” Jane described her endless fascination with understanding how the architecture of the network can affect pollination interactions and the robustness of the system to species loss. Jane spent her second post doc working on the biological control of invasive plants. During this project, Jane spent time in New Zealand, which proved to be a contrast to the hot, sometimes gruelling nature of her project in Costa Rica. She spoke of her time in New Zealand, describing it as one of her favourite places in the world: “I lived a life of eternal summer – it was easy to live in a little house in paradise and travel round the country doing experiments.”

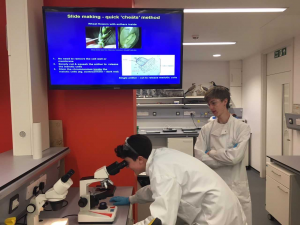

After ten years travelling the world and living out of a rucksack, Jane returned to the UK, where in 1996 she obtained her lectureship at Bristol. Jane stressed that returning to the UK did not mean forfeiting amazing wildlife encounters, mentioning the amazing views of peregrines that can liven up staff meetings in the sky lounge. From 2012 to 2016, she became Head of the School of Biological Sciences at the University of Bristol. This position came with some challenges, including leading the movement of the school to the new Life Sciences Building that we know and love today. Nowadays, one of her favourite parts of the job is teaching – especially first year lectures. Jane also enjoys seeing students from all around the world progress through university to do PhDs, and she loves to see the effect that the publishing of a big research paper can have on the young scientists leading the project.

“I asked Jane what advice she would give to students interested in getting into academia. Her reply was “it’s absolutely worth it!”.”

Outside of her work, Jane enjoys gardening, dog walks and getting out and about in nature with her family; having recently been searching for short-eared owls on the Severn estuary. Professor Memmott describes herself as “always reading”- she enjoys novels, adventure books and books related to ecology. She also mentioned that her two teenagers take up a lot of her attention. I asked Jane what advice she would give to students interested in getting into academia. Her reply was “it’s absolutely worth it!”. She spoke of the “tremendous freedom” associated with being able to do your own research but warned to be prepared to put up with lots of rejection. “You can learn a lot from your rejections – it’s not wasted time.”

The British Ecological Society is the oldest ecological society in the world. The society has six journals including the Journal of Ecology and Ecology and Evolution, and it provides research grants and supports ecologists in their early careers. Jane joined the British Ecological Society as a PhD student and has been a member ever since. She described the society as having been very supportive over the years; providing her with a grant that enabled her to employ a field assistant to help carry out the field work that began all of her pollination research. I asked Jane what it meant to her to be elected as the president of the British Ecological society. She replied, “I’m very honoured – I’m still smiling!”.

Written by Jenny Stewart, MSci Zoology