This Monday Professor Tracy Lawson from the University of Essex talked to students and academic staff in Bristol about her last findings in the survey of stomata behaviour as a response to different environmental stimuli.

This Monday, Professor Tracy Lawson from the School of Biological Sciences of the University of Essex talked to students and academic staff of the LSB in Bristol about her last findings in the survey of stomatal behaviour as a response to different environmental stimuli. During the last 6 years, she and the members of her lab have been working on stomata, water assimilation rates and CO2 gain, the speed of response of stomata in different light conditions, and the importance of studying this topic according to current and future global environmental conditions such as increases in temperatures worldwide, more food production using less land, changing rainfall patterns and lack of water sources for demanding irrigation crops.

During the first part of her talk, Professor Lawson talked about how different plants have different patterns of stomatal behaviour and how these respond differently according to plant phenotype and environmental conditions. Just to mention an example, rice can get a maximum carbon assimilation rate of 95% in only 10 minutes in comparison to Ginkgo biloba that takes one hour to reach a similar rate.

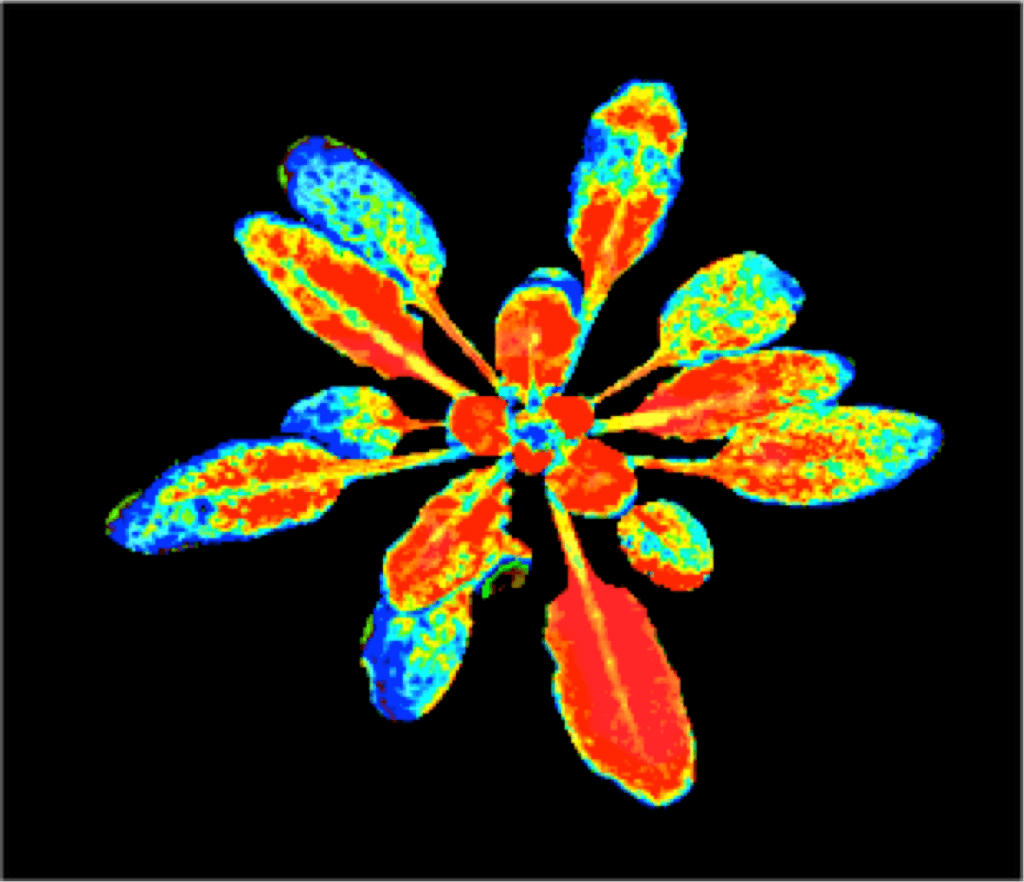

To know more about how plants respond to light fluctuations and climate, Professor Lawson mimicked natural fluctuations in light over a diurnal period to examine the effect on the photosynthetic processes and growth of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana). She compared the plant’s behaviour under square wave light and fluctuating light conditions. Under the first treatment, plants responded with thicker leaves, more photosynthetic efficiency, better leaf structure and more proteins associated with electron transport. Plants under the second treatment produced thinner leaves, lower light absorption and slower growth. Under both conditions, plants maintained similar photosynthetic rates.

However, these results highlight that there is a negative feedback control of photosynthesis resulting in a decrease of diurnal carbon assimilation under fluctuating light conditions and that plants under square wave light fail as predictors of performance under realistic light regimes.

The following part of her talk was about the impact of dynamic growth light on stomatal acclimation and behaviour. Professor Lawson assessed the impact of growth light regime on stomatal acclimation and gas exchange growing Arabidopsis plants in three different lighting regimes:

- with the same average daily intensity,

- fluctuating with a fixed pattern of light, fluctuating with a randomized pattern of light (sinusoidal), and non-fluctuating (square wave).

With this experiment she and her research team demonstrated that gs (stomatal conductance to water vapour) acclimation is influenced by pattern and intensity of light, modifying the stomatal kinetics at different times of the day and resulting in differences in the rapidity and magnitude of the gs response. They quantified the response to a signal that uncouples variation in CO2 assimilation and gs over most of the diurnal period. This can be translated as 25% water loss during the day without CO2 assimilation. The gs response can be characterized by a Gaussian element when incorporated into the Ball-Berry model to predict the gs in a dynamic environment.

Professor Lawson concluded that acclimation of gs to light could be an important strategy for maintaining carbon fixation and overall plant water status and should be considered to infer responses of crops under field conditions.

Written by Carlos Gracida Juarez (Biological Sciences PhD)